Prism of Fair Value Investing – The legends

💡 Discover Powerful Investing Tools

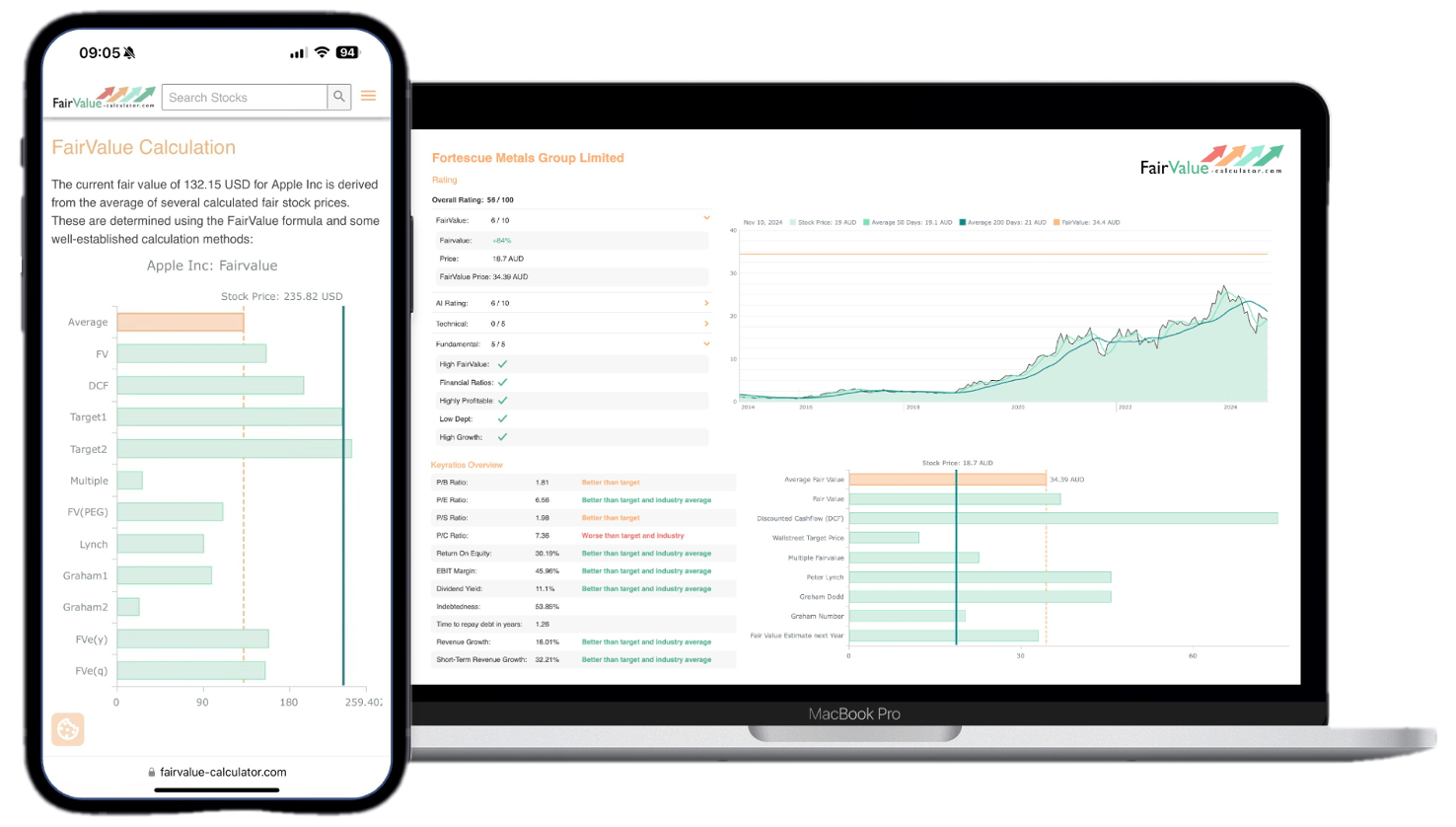

Stop guessing – start investing with confidence. Our Fair Value Stock Calculators help you uncover hidden value in stocks using time-tested methods like Discounted Cash Flow (DCF), Benjamin Graham’s valuation principles, Peter Lynch’s PEG ratio, and our own AI-powered Super Fair Value formula. Designed for clarity, speed, and precision, these tools turn complex valuation models into simple, actionable insights – even for beginners.

Learn More About the Tools →“All Intelligent Investing is value investing – acquiring more than you are paying for” – Charlie Munger

🚀 Test the Fair Value Calculator Now!

Find out in seconds whether your stock is truly undervalued or overpriced – based on fundamentals and future growth.

Try it for Free →2+2 = 5!! Ok, it is not actually 5 and we are not here to change the rules of mathematics. However, what we do want to highlight is the undeniability of universal truths and processes. In life, as in mathematics, we often have to follow certain, predefined processes and procedures for efficiency in our tasks. Stray out of the path and you will end up in a gigantic mess that cannot be salvaged in most parts.

Explore our most popular stock fair value calculators to find opportunities where the market price is lower than the true value.

- Peter Lynch Fair Value – Combines growth with valuation using the PEG ratio. A favorite among growth investors.

- Buffett Intrinsic Value Calculator – Based on Warren Buffett’s long-term DCF approach to determine business value.

- Buffett Fair Value Model – Simplified version of his logic with margin of safety baked in.

- Graham & Dodd Fair Value – Uses conservative earnings-based valuation from classic value investing theory.

- Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Value – Learn the core difference between what a company’s really worth and what others pay.

- Intrinsic Value Calculator – A general tool to estimate the true value of a stock, based on earnings potential.

- Fama-French Model – For advanced users: Quantifies expected return using size, value and market risk.

- Discount Rate Calculator – Helps estimate the proper rate to use in any DCF-based valuation model.

Look at any aspect of life in general; pasta must be boiled before adding sauce: you cannot add sauce to the water and then boil the pasta. A manual transmission car or motorcycle must be started in neutral gear; it will never start in first gear. A water tap must be opened anti-clockwise and closed clockwise, cannot do the opposite unless you want to break the tap.

Life is governed by rules and processes, either naturally imposed or decided by man and universally accepted. Efficiency and subsequent accomplishment of any task are determined by how well you follow the rules.

Financial markets are a whole different beast altogether and have demonstrated time and again to not be governed by these rules, either natural or man-made. An investor follows certain rules and can make money whereas another investor can break those exact rules and still make money. Markets are like those complex equations that can never be solved, a vehicle that cannot be driven, and a fair maiden that cannot be wooed.

Thus, it is a foregone conclusion that there is no single way to beat the markets. However, over the course of decades, certain styles and frameworks have emerged that if incorporated, have proven to ease the journey for most investors. Value investing is one such framework.

Value holds different meanings across the globe. It is highly subjective in nature. One man’s garbage is another man’s treasure. What goes for value is often a confluence of factors; local, cultural, language, demand and supply, etc. The best example of value is sports memorabilia. Baseball cards and signed balls hold tremendous value in the USA but would be worthless in African and Asian countries where the sport is not played. Similarly, cricket memorabilia will hold high value in India, Australia, and England but hold no value in the USA.

Throughout the course of this piece and subsequent articles in this series, we take a look at legendary value investors, each with their own understanding of the value and their attempts at making value investing objectives.

Readers may take note that markets often move in cycles and evolve and change over time. Railways used to be a dominant industry a century ago; its place is now taken by tech. Some other, unconceivable industry may dominate a century from now. Value and its perception also change across industries. The frameworks provided in this piece and subsequent articles were designed around the dominant industries of that time. While their effectiveness might have dulled, the underlying principles remain solid and timeless and readers are recommended to incorporate the same in their personal investing philosophy.

At Fairvalue Calculator, we will provide you with objective calculations and methodologies for all frameworks of value investing. The subjective part however has to be internal. That is what makes value investing successful. Investors can look at the same data but arrive at different conclusions for the same stock and still make money. Figure out your investing philosophy because only that will allow you to stay invested through drawdowns and if you can survive drawdowns successfully, success is all but guaranteed. With that said, let’s look at our first framework.

Book Value Investing: Margin of Safety

Everybody has heard of Benjamin Graham. The father of value investing, as he is known, not only wrote a seminal piece on value investing and investor behavior but also practiced what he preached, managing money for himself and his clients.

Graham introduced the concept of Mr. Market, an irrational being who buys and sells securities at different prices each day. On most days, the prices would be fair and normal. However, on some days, Mr. Market would become irrational and quote too low or too high a price than what is fair. These days were opportunities where investors could buy or sell their securities respectively.

To better identify the days when Mr. Market was being irrational, Graham introduced the concept of intrinsic value and margin of safety. Through careful analysis of financial statements, one could determine the actual value of the company per share (book value) and if the traded price of the share was less than the actual value, the company was undervalued and vice versa.

Philosophy Caveat

Readers must note that this investing philosophy was conceived in the 1930s and 40s which were times of upheaval. The world was emerging from a great war, a great depression, and was soon looking at another great war. Manufacturing and heavy industries were the dominant industries at that time.

Heavy industries like iron and steel, automobiles, capital goods, etc. tend to be asset-heavy companies. A lot of their investments and net worth are locked in the land, factories, inventory, and work-in-progress activities. Book value captures all these details. It was easier to estimate and calculate the value of a heavy machinery company. One had to look at the land where the factories are, get the land rates from the local realtor, get construction or resale costs of a factory building, determine the salvage value of the machinery, and have a fair estimation of the book value of the company. Should one buy the company outright and liquidate it, the realized value would be the book value.

So in the above scenario, if the book value of the company was $100 per share and the traded share price was $75 per share, one could theoretically buy the company at $75 per share and liquidate it to realize a profit of $25 per share. Again, readers must remember that markets were quite inefficient as compared to today. They were still physical at that time as compared to the electronic ones today. Physical paper shares were traded and information was not freely available. This gave Graham the edge to make use of the inefficiency to buy shares at a cheap discount to their fair value.

Graham’s successes

Graham adopted a simple process for his investing decisions. He would buy securities at 50 cents on the dollar, basically at a 50% discount to book value, and sell them when the prices approached fair value. So a typical transaction would be to buy at $50 dollars for a book value of $100 per share and sell once the price crosses $100 per share. He would not allocate more than 5% of his net assets to one company.

It was a simple philosophy but it worked, allowing Graham and his investors to achieve 20% annualized returns on a consistent basis. However his biggest success, and one which he achieved by breaking all the rules was GEICO.

The Government Employees Insurance Company is a private American auto insurance company founded in 1936 and headquartered in Chevy Chase, Maryland. Somewhere in 1948, Graham and his partners chanced upon an opportunity to acquire 50% of this growing business.

Breaking their rules, they invested 25% of their assets in this single security and again breaking their rules, held on until their investment value of $712,500 became $400 million in 25 years. Was he lucky or was it a good investment decision? Difficult to answer, even by Graham himself. However, they were not bad investors considering the 20% annualized returns generated even without GEICO.

Most of us might not be as lucky. However with proper preparation and some support from fairvalue, one might hit upon such opportunities, albeit rarely. Remember, all it takes is one stock to make your fortunes. In football parlance, consider it a penalty but without any goalkeeper in sight. Happens very rarely, but it does.

Graham’s failures

Benjamin Graham was a successful investor even if you exclude GEICO. However, all successful investors make mistakes even with all the experience under their belts. No one is immune from the vagaries of the market. However, what determines your survival is your risk exposure and your ability to diversify and control your emotions.

Graham went into the 1929 crash extremely leveraged. His normal strategy was to hold equal short positions to his long positions forming a kind of hedge. In 1929, at the peak of the bull market, he was swayed by his emotions of irrational exuberance and buoyed by his previous successes took on what was common during that period, some margin funding.

Then the crash came. Graham lost 70% of his fund from 1929 to 1932. In comparison Dow lost 80% of its value so while Graham did beat the markets; the loss was still significant to recover from. He managed to recover the losses by 1935, an amazing feat but was so burnt by the experience that he swore off leverage completely and became an even more conservative investor.

Application in the real world

Benjamin Graham, with its philosophy, may have generated 20% returns annually for his investors but if you were to apply the same vanilla philosophy, you will either not be invested or will generate much inferior returns. Warren Buffett, the world’s largest value investor and a disciple of Benjamin Graham quoted in one of his interviews for Fortune Magazine in 1988, that if he had listened only to Ben, he would have been a lot poorer.

On fairvalue, you can check this out for yourself. Let us look at Caterpillar Inc., an American construction equipment manufacturer. Its book value is $35.16 per share and it is currently traded at $235, almost 7x its book value. The stock was last below $35 per share in 2009 during the great financial crisis and I can tell you with certainty that the book value of the company at that time was less than $35 per share.

Even when you compare it with the industry and target, it is fairly overvalued. Yet this has been a market leader and as an investor following Benjamin Graham’s value investing strategy, you may have never invested in it.

This is an asset-heavy business. The book value investing philosophy fails even more spectacularly when you take asset-light businesses into account like technology. Let us look at Apple Inc. (You knew where I was going with this, weren’t you?)

Apple has a book value of only $3.95 per share. It traded below this level way past even before the great financial crisis. After the introduction of the iPhone its share price has never touched single digits forget trading below the book value. As a value investor, one might have missed out on investing in Apple stock altogether.

Solution for our investors

As we have mentioned in this article, while the philosophy may have failed to keep pace with time, the underlying principles are still sound. You, my dear reader, as an investor need to incorporate a certain margin of safety in your investments. This can be done by investing at a value much lower than its fair value.

Fair value is not determined by book value alone. As you will subsequently see during the series, different definitions and objective interpretations of value will emerge, and today, one can use all of them to build a consensus on whether the stock is undervalued or overvalued.

Fairvalue calculator offers just that. It calculates fair value using various fair value methods used both by our legendary investors as well as current analysts and presents it to you in an easy-to-read manner.

For e.g. in the above example, one can see that the caterpillar is overvalued by all measures. Except for discounted cash flow (DCF), its stock price is trading much above the fair value. Ideally, you would want the stock price to trade below the consensus levels. In the above scenario, if Caterpillar were to trade near 100, it would meet almost all fair value scenarios and would make for an excellent investment with a decent margin of safety.

Here is one more example: Volkswagen, the German automobile manufacturer. It is trading at levels well below fair values calculated by most methods and has a significant margin of safety. It is also backed by physical assets making for an excellent implementation of a tweaked version of Graham’s strategy.

Last words

Dear Reader, fairvalue calculator can assist you with every objective aspect of investing, especially value investing. It is the subjective part that one needs to develop and incorporate into investing strategy in order to fight through market upheavals and stay invested throughout drawdowns.

In the Volkswagen example, one can look at whether the company is meeting various criteria that will enable it to realize its fair value. Are their sales growing? Have they solved their climate fraud issue? Is management backing up its words with actions? All of this information is easily available, both on the news section of fairvalue calculator as well as on Google. As food for thought, here is some news about Volkswagen: Volkswagen’s 2023 sales outlook blows past forecast.

This clearly shows that Volkswagen is doing something right, which improves the probability that it may realize its fair value in the near to medium term. Remember investing is a long game and one may have to wait patiently with undervalued shares until the market realizes its potential fair value. The flip side however is that if the company is continuing to do well, one can accumulate a sizeable position in an undervalued stock before the stock makes its move.

In financial markets, nothing is guaranteed, hence the use of the word probability. However with fairvalue calculator, as an investor, you can certainly use our tools to improve your edge and thus improve the probability of successful investment decisions falling in your favor. In the next chapter of this series, we look at what improvements Graham’s most famous disciple and current market leader in value investing, Mr. Warren Buffett made on this original value investing strategy to carve out his own niche and achieve success in value investing.