In finance and accounting, the concepts of fair value and market value play pivotal roles in asset valuation, financial reporting, and investment decisions. While these terms are sometimes used interchangeably in casual conversation, they represent distinct approaches to determining the worth of assets, each with its own methodologies, applications, and implications.

This article aims to provide a comprehensive exploration of fair value and market value, delving into their definitions, applications, and the crucial differences between them. By understanding these concepts, financial professionals, investors, and business leaders can make more informed decisions, ensure compliance with accounting standards, and gain deeper insights into the true value of assets and investments.

As we navigate through the complexities of these valuation methods, we’ll examine their theoretical underpinnings, practical applications, and the ongoing debates surrounding their use in various financial contexts. Whether you’re a seasoned financial expert or a newcomer to the field, this article will equip you with the knowledge to distinguish between fair value and market value and understand their significance in today’s financial landscape.

2. Defining Fair Value

2.1 The Concept of Fair Value

Fair value is a rational and unbiased estimate of the potential market price of an asset or liability. It represents the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date. This concept is fundamental to modern accounting practices and is designed to provide a more accurate representation of an asset’s or liability’s true economic value.

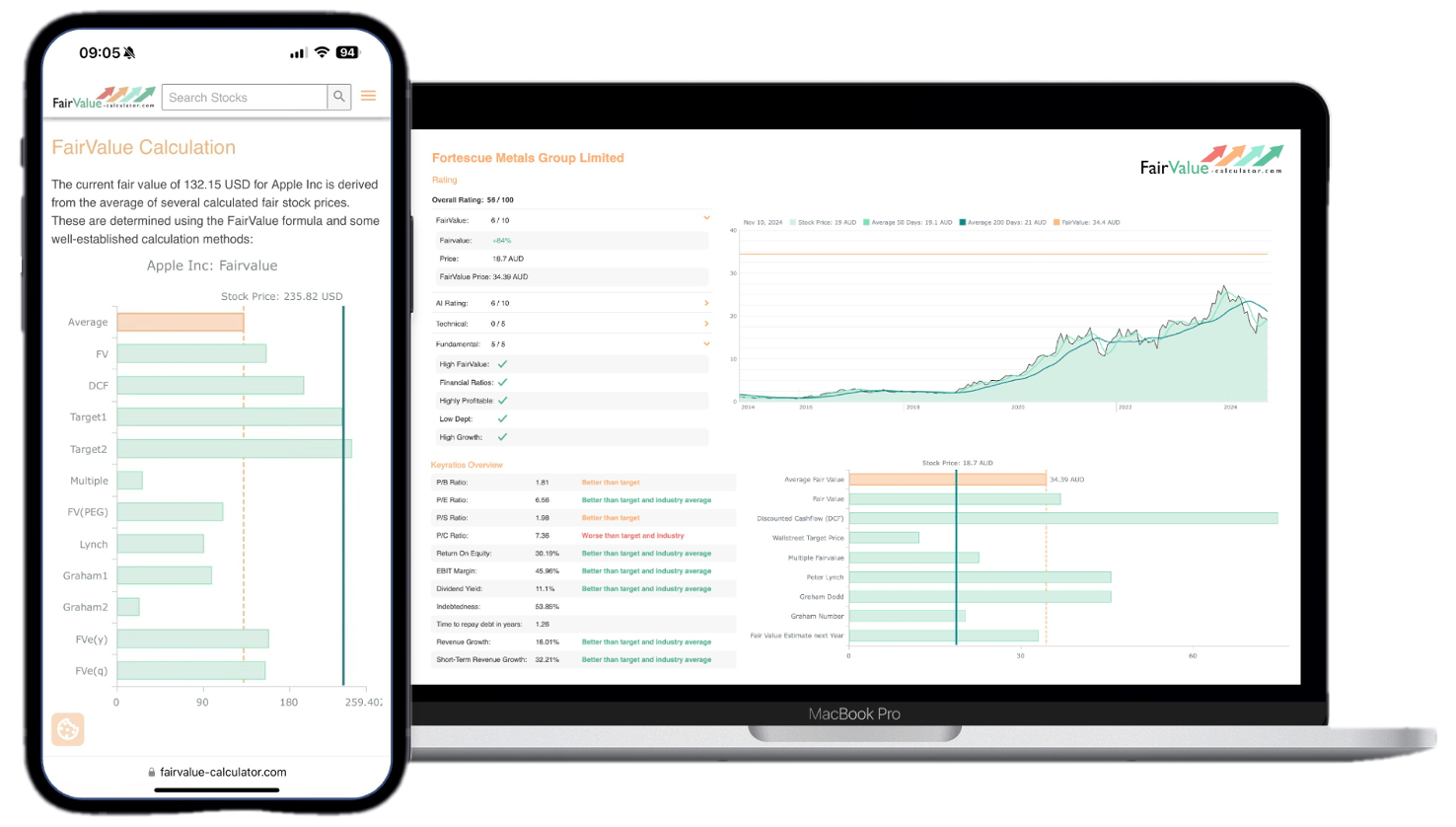

Explore our most popular stock fair value calculators to find opportunities where the market price is lower than the true value.

- Peter Lynch Fair Value – Combines growth with valuation using the PEG ratio. A favorite among growth investors.

- Buffett Intrinsic Value Calculator – Based on Warren Buffett’s long-term DCF approach to determine business value.

- Buffett Fair Value Model – Simplified version of his logic with margin of safety baked in.

- Graham & Dodd Fair Value – Uses conservative earnings-based valuation from classic value investing theory.

- Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Value – Learn the core difference between what a company’s really worth and what others pay.

- Intrinsic Value Calculator – A general tool to estimate the true value of a stock, based on earnings potential.

- Fama-French Model – For advanced users: Quantifies expected return using size, value and market risk.

- Discount Rate Calculator – Helps estimate the proper rate to use in any DCF-based valuation model.

The key aspects of fair value include:

- It’s based on current market conditions and expectations.

- It assumes a hypothetical transaction between willing parties.

- It considers the highest and best use of an asset.

- It takes into account all relevant available information.

2.2 Fair Value in Accounting Standards

Fair value has gained prominence in accounting standards over the past few decades, particularly with the introduction of fair value accounting. Both the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and the United States Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (US GAAP) have incorporated fair value measurements into their frameworks.

💡 Discover Powerful Investing Tools

Stop guessing – start investing with confidence. Our Fair Value Stock Calculators help you uncover hidden value in stocks using time-tested methods like Discounted Cash Flow (DCF), Benjamin Graham’s valuation principles, Peter Lynch’s PEG ratio, and our own AI-powered Super Fair Value formula. Designed for clarity, speed, and precision, these tools turn complex valuation models into simple, actionable insights – even for beginners.

Learn More About the Tools →IFRS 13 and ASC 820 (under US GAAP) provide guidance on fair value measurement. These standards define fair value, set out a framework for measuring fair value, and require disclosures about fair value measurements. The goal is to increase consistency and comparability in fair value measurements and related disclosures across different entities and jurisdictions.

2.3 Methods of Determining Fair Value

Determining fair value often involves complex calculations and judgments. Some common methods include:

- Market Approach: This method uses prices and other relevant information generated by market transactions involving identical or comparable assets or liabilities.

- Income Approach: This technique converts future amounts (e.g., cash flows or earnings) to a single current (discounted) amount, reflecting current market expectations about those future amounts.

- Cost Approach: This approach reflects the amount that would be required currently to replace the service capacity of an asset (often referred to as the current replacement cost).

The choice of method depends on the nature of the asset or liability being valued, the availability of data, and the specific circumstances of the valuation.

3. Understanding Market Value

3.1 The Concept of Market Value

Market value, also known as market price, is the price at which an asset would trade in a competitive auction setting. It is the estimated amount for which a property would be exchanged on the date of valuation between a willing buyer and a willing seller in an arm’s-length transaction after proper marketing wherein the parties had each acted knowledgeably, prudently, and without compulsion.

Key characteristics of market value include:

- It represents the actual transactional price in an open and competitive market.

- It’s based on the principle of supply and demand.

- It can fluctuate rapidly based on market conditions and sentiment.

- It’s directly observable for actively traded assets.

3.2 Factors Influencing Market Value

Numerous factors can influence the market value of an asset:

- Supply and Demand: The fundamental economic principle of supply and demand plays a crucial role in determining market value.

- Economic Conditions: Broader economic factors such as interest rates, inflation, and economic growth can significantly impact market values.

- Market Sentiment: Investor psychology and market sentiment can lead to short-term fluctuations in market value.

- Asset-Specific Factors: For physical assets like real estate, factors such as location, condition, and potential for future development can affect market value.

- Regulatory Environment: Changes in laws and regulations can impact the market value of certain assets or industries.

3.3 Market Value in Real Estate and Investments

In real estate, market value is often determined through comparative market analysis, where recent sales of similar properties in the same area are used as benchmarks. For publicly traded securities, market value is readily observable as the current trading price on exchanges.

In the context of investments, market value is crucial for:

- Portfolio Valuation: Investors and fund managers use market values to assess the current worth of their investment portfolios.

- Performance Measurement: Market values are used to calculate returns and compare investment performance.

- Risk Assessment: Fluctuations in market value help in assessing the volatility and risk associated with an investment.

4. Key Differences Between Fair Value and Market Value

4.1 Conceptual Differences

While fair value and market value can sometimes align, they are conceptually distinct:

- Theoretical vs. Actual: Fair value is a theoretical construct based on hypothetical transactions, while market value represents actual transactional prices.

- Stability: Fair value tends to be more stable as it considers long-term fundamentals, while market value can be more volatile, reflecting short-term market sentiments.

- Perspective: Fair value attempts to capture the intrinsic value of an asset considering all available information, while market value reflects the current market consensus.

- Time Horizon: Fair value often takes a longer-term view, while market value represents the immediate price point.

4.2 Methodological Differences

The methods used to determine fair value and market value can differ significantly:

- Fair Value Methods:

- Often involve complex valuation models

- May use discounted cash flow analysis

- Consider unobservable inputs (Level 3 in the fair value hierarchy)

- Require professional judgment and expertise

- Market Value Methods:

- Primarily based on observable market data

- Use comparative analysis of similar assets

- Reflect current market conditions and transactions

- More straightforward for actively traded assets

4.3 Application in Different Contexts

Fair value and market value find applications in different contexts:

- Financial Reporting: Fair value is widely used in financial statements to report the value of certain assets and liabilities, especially under IFRS and US GAAP.

- Investment Decisions: Market value is crucial for day-to-day investment decisions, especially in liquid markets like stock exchanges.

- Real Estate: Both concepts are used in real estate, with market value being more common in property transactions and fair value in certain accounting contexts.

- Business Valuation: Fair value is often used in business combinations and impairment testing, while market value is relevant for publicly traded companies.

- Regulatory Compliance: Fair value measurements are required for certain regulatory reporting, while market values are used in other regulatory contexts, such as determining capital requirements for financial institutions.

5. Fair Value in Financial Reporting

5.1 IFRS and US GAAP Requirements

Both IFRS and US GAAP have extensive requirements for fair value measurements in financial reporting. Key aspects include:

- IFRS 13 (Fair Value Measurement): This standard provides a single framework for measuring fair value and requires disclosures about fair value measurements.

- ASC 820 (Fair Value Measurements and Disclosures): The US GAAP equivalent to IFRS 13, which defines fair value, establishes a framework for measuring it, and expands disclosures about fair value measurements.

- Application Areas: Fair value is used in various areas of financial reporting, including:

- Financial instruments

- Investment Properties

- Biological assets

- Impairment testing of non-financial assets

- Business combinations

5.2 Fair Value Hierarchy

Both IFRS and US GAAP establish a fair value hierarchy that categorizes the inputs to valuation techniques used to measure fair value into three levels:

- Level 1: Quoted prices in active markets for identical assets or liabilities.

- Level 3: Unobservable inputs for the asset or liability.

This hierarchy prioritizes the inputs used in valuation techniques, with Level 1 being the most reliable and Level 3 requiring the most judgment.

5.3 Challenges in Fair Value Reporting

While fair value reporting aims to provide more relevant financial information, it comes with several challenges:

- Complexity: Fair value measurements can be complex, especially for assets and liabilities without active markets.

- Subjectivity: Level 3 measurements involve significant management judgment, which can lead to potential bias or manipulation.

- Volatility: Fair value measurements can introduce volatility into financial statements, especially during periods of market turbulence.

- Audit Difficulties: Auditors face challenges in verifying fair value measurements, particularly those based on complex models or unobservable inputs.

- Cost and Effort: Implementing fair value measurements can be resource-intensive, requiring specialized expertise and sophisticated valuation models.

6. Market Value in Practice

6.1 Market Value in Real Estate

In the real estate sector, market value plays a crucial role:

- Property Appraisals: Real estate appraisers use market value as a key metric in property valuations.

- Comparative Market Analysis (CMA): Realtors use CMAs to determine the market value of properties based on recent sales of similar properties in the area.

- Property Taxes: Many jurisdictions base property taxes on the market value of real estate.

- Mortgage Lending: Lenders use market value assessments to determine loan-to-value ratios and mortgage terms.

6.2 Market Value in Securities and Investments

In financial markets, market value is a fundamental concept:

- Stock Prices: The market value of publicly traded stocks is readily observable as the current trading price.

- Bond Valuation: While bonds have a face value, their market value fluctuates based on interest rates and issuer creditworthiness.

- Mutual Funds: The Net Asset Value (NAV) of mutual funds is calculated based on the market value of the underlying securities.

- Portfolio Management: Investment managers use market values to assess portfolio performance and make buy/sell decisions.

6.3 Limitations of Market Value

While market value is widely used, it has several limitations:

- Volatility: Market values can be highly volatile, especially in times of economic uncertainty or market panic.

- Liquidity Issues: For illiquid assets, observed market values may not accurately reflect the true value due to thin trading.

- Market Inefficiencies: Market values can be distorted by factors such as information asymmetry, market manipulation, or irrational investor behavior.

- Short-Term Focus: Market values often reflect short-term sentiment rather than long-term fundamental value.

- Bubble Scenarios: In asset bubbles, market values can deviate significantly from intrinsic values, leading to potential mispricing.

7. The Interplay Between Fair Value and Market Value

7.1 When Fair Value Equals Market Value

In ideal conditions, fair value and market value should align:

- Efficient Markets: In highly efficient markets with perfect information, the market price should reflect all available information, aligning with fair value.

- Actively Traded Assets: For liquid assets traded in active markets, fair value is often directly derived from market prices (Level 1 inputs in the fair value hierarchy).

- Orderly Transactions: When transactions occur between willing buyers and sellers without distress, market value often represents fair value.

7.2 Scenarios Where They Differ

However, there are many situations where fair value and market value can diverge:

- Market Inefficiencies: In less efficient markets, prices may not fully reflect all available information, causing a divergence between fair value and market value.

- Illiquid Assets: For assets without active markets, fair value may need to be estimated using valuation techniques, potentially differing from sporadic market transactions.

- Distressed Sales: In forced or distressed sales, the market value may not represent fair value as defined in accounting standards.

- Long-Term vs. Short-Term Perspectives: Fair value often takes a longer-term view, while market value can be influenced by short-term factors and sentiment.

- Private Companies: For non-publicly traded companies, fair value estimates may differ significantly from potential market values due to a lack of market data.

7.3 Implications for Financial Decision-Making

Understanding the relationship and potential differences between fair value and market value is crucial for financial decision-making:

- Investment Strategies: Value investors often look for discrepancies between fair value and market value to identify undervalued assets.

- Financial Reporting: Companies need to be aware of how fair value measurements might differ from observable market prices and explain these differences in financial disclosures.

- Risk Management: Recognizing when market values deviate significantly from fair values can help in identifying and managing financial risks.

- Mergers and Acquisitions: In M&A transactions, understanding both fair value and market value is crucial for negotiations and deal structuring.

- Regulatory Compliance: Financial institutions need to consider both fair value and market value in risk assessment and regulatory reporting.

8. Criticisms and Controversies

8.1 Debates Surrounding Fair Value Accounting

Fair value accounting has been the subject of significant debate, especially following the 2008 financial crisis:

- Procyclicality: Critics argue that fair value accounting can exacerbate economic downturns by forcing writedowns during market declines, potentially creating a “death spiral” effect.

- Reliability Concerns: For assets without active markets, fair value measurements can be highly subjective and potentially manipulated.

- Volatility in Financial Statements: Fair value accounting can introduce significant volatility into financial statements, potentially obscuring underlying business performance.

- Complexity and Cost: Implementing fair value measurements can be complex and costly, especially for smaller entities.

- Auditing Challenges: Verifying fair value measurements presents challenges for auditors, particularly for Level 3 inputs.

8.2 Market Value Volatility and Its Impact

The volatility of market values also raises concerns:

- Short-Termism: Excessive focus on market values can lead to short-term thinking and decision-making at the expense of long-term value creation.

- Market Manipulation: In some cases, market values can be influenced by market manipulation or speculation, leading to prices that don’t reflect fundamental value.

- Systemic Risk: Rapid changes in market values, especially in financial markets, can contribute to systemic risk and financial instability.

- Behavioral Biases: Market values can be influenced by investor psychology and behavioral biases, potentially leading to irrational pricing.

- Liquidity Concerns: In times of market stress, rapid declines in market values can lead to liquidity crunches and forced selling, further exacerbating price declines.

9. Case Studies

9.1 Fair Value Application in the 2008 Financial Crisis

The 2008 financial crisis provided a stark illustration of the challenges and controversies surrounding fair value accounting:

Background:

- Leading up to the crisis, many financial institutions held significant portfolios of mortgage-backed securities and other complex financial instruments.

- These assets were often valued using fair value accounting principles.

Crisis Unfolds:

- As the U.S. housing market collapsed, the market for these securities became illiquid.

- Fair value accounting requires institutions to mark these assets down to their current market values, which were often significantly lower than their original costs.

Consequences:

- These write-downs led to substantial losses on bank balance sheets.

- Some argued that fair value accounting exacerbated the crisis by forcing banks to recognize losses on assets they intended to hold to maturity.

- Others contended that fair value accounting provided necessary transparency about the true state of bank balance sheets.

Regulatory Response:

- In response to the crisis, both FASB and IASB provided additional guidance on fair value measurements in inactive markets.

- This guidance allowed for more flexibility in determining fair values when markets are not active or transactions are not orderly.

Lessons Learned:

- The crisis highlighted the challenges of applying fair value accounting in illiquid markets.

- It sparked ongoing debates about the appropriate use of fair value accounting for financial instruments.

- The experience led to refinements in accounting standards and regulatory approaches to fair value measurements.

9.2 Market Value Fluctuations in the Real Estate Market

The real estate market provides an excellent case study of how market values can fluctuate and diverge from long-term fair values:

The Housing Bubble (2000-2007):

- In the early 2000s, U.S. housing prices experienced rapid appreciation.

- Market values of homes in many areas far exceeded historical norms and traditional valuation metrics.

- This period illustrated how market values can become detached from fundamental fair values.

The Crash (2008-2012):

- The bursting of the housing bubble led to a sharp decline in market values.

- In many areas, market values fell below replacement costs or intrinsic values based on rental income.

- This period demonstrated how market panic can drive prices below fair value estimates.

Recovery and Regional Variations (2013-Present):

- The recovery of the housing market has been uneven across different regions.

- Some markets have seen market values rebound to or exceed pre-crisis levels.

- Other areas have experienced slower recoveries, with market values remaining below peak levels.

Implications:

- This case study highlights the volatility of market values, especially in cyclical markets like real estate.

- It demonstrates the importance of considering long-term fundamentals (akin to fair value concepts) alongside current market values.

- The divergence between market values and fundamental values during both the boom and bust phases underscores the limitations of relying solely on market prices for valuation.

10. Future Trends and Developments

10.1 Technological Advancements in Valuation

The future of both fair value and market value determination is likely to be shaped by technological advancements:

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning:

- AI algorithms can process vast amounts of data to improve fair value estimates.

- Machine learning models can identify patterns and relationships that human analysts might miss.

- These technologies could enhance the accuracy and consistency of valuations.

- Big Data Analytics:

- The increasing availability of big data can provide more inputs for both fair value and market value determinations.

- Real-time data analysis could lead to more dynamic and responsive valuations.

- Blockchain Technology:

- Blockchain could provide more transparent and immutable records of transactions.

- This could enhance the reliability of market value data and potentially streamline fair value calculations.

- Automated Valuation Models (AVMs):

- Particularly in real estate, AVMs are becoming more sophisticated.

- These models could bridge the gap between market values and fair value estimates.

- Natural Language Processing (NLP):

- NLP could be used to analyze qualitative information (e.g., news reports, and social media) that might impact fair values.

- This could lead to more comprehensive and nuanced valuations.

10.2 Regulatory Changes and Their Impact

The regulatory landscape surrounding fair value and market value is likely to continue evolving:

- Increased Standardization:

- Regulators may push for more standardized approaches to fair value measurements to enhance comparability across entities and jurisdictions.

- Enhanced Disclosure Requirements:

- There may be calls for more detailed disclosures about valuation methodologies and assumptions, particularly for Level 3 fair value measurements.

- Integration of Non-Financial Factors:

- Growing emphasis on ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) factors could lead to their incorporation into fair value measurements.

- Regulatory Technology (RegTech):

- The use of technology to enhance regulatory processes could lead to more real-time monitoring of valuations and market values.

- Global Convergence:

- Continued efforts towards global accounting standard convergence could impact fair value measurement practices worldwide.

- Response to Market Volatility:

- Future financial crises or periods of extreme market volatility could prompt a regulatory reassessment of fair value accounting rules.

- Cybersecurity Considerations:

- As valuation processes become more technology-dependent, regulators may introduce new requirements around data security and integrity in valuation processes.

Final words

The concepts of fair value and market value, while related, serve distinct purposes in the realms of finance, accounting, and investment. Market value represents the current price at which an asset would trade in a competitive market, reflecting immediate supply and demand dynamics. Fair value, on the other hand, aims to provide a more stable and comprehensive measure of an asset’s worth, considering all relevant factors and potential market participants.

Understanding the differences between these two concepts is crucial for several reasons:

- Financial Reporting: Fair value measurements play a significant role in modern accounting standards, impacting how assets and liabilities are reported on financial statements.

- Investment Decisions: Investors often seek discrepancies between fair value estimates and market values to identify potential investment opportunities.

- Risk Management: Recognizing when market values deviate significantly from fair value estimates can help in identifying and managing financial risks.

- Regulatory Compliance: Both concepts are important in various regulatory contexts, from financial institution capital requirements to tax assessments.

- Business Valuation: In contexts such as mergers and acquisitions or dispute resolution, understanding both fair value and market value is essential.

As we’ve explored, both concepts have their strengths and limitations. Market values provide real-time information about asset prices but can be subject to short-term volatility and market inefficiencies. Fair value measurements aim to provide a more stable and comprehensive valuation but can involve significant judgment and complexity.

Looking to the future, technological advancements and evolving regulatory landscapes are likely to shape how we approach both market and fair value determinations. The increasing use of artificial intelligence, big data analytics, and automated valuation models may enhance the accuracy and efficiency of valuations. At the same time, regulatory changes may seek to address some of the challenges and controversies surrounding fair value accounting that came to the fore during events like the 2008 financial crisis.

While fair value and market value may sometimes align, understanding their distinct characteristics and applications is essential for anyone involved in finance, accounting, or investment. By appreciating the nuances of these concepts, professionals can make more informed decisions, provide more accurate financial reporting, and navigate the complex landscape of modern finance with greater confidence and insight.